Virtual Training

~ Subscribe to our You Tube channel for our great virtual training sessions ~

Virtual Presentations

The Society currently offers virtual presentations through Zoom or in person. Our presentations include:

The Forgotten Squadron - The Naval Arms Race of the War of 1812

Food of the Royal Navy during the War of 1812

Small Arms on the Great Lakes during the War of 1812

Traditional Seamanship - Knots, Sailing, and Material Culture

Have us present to your group!

Library

The Society is primarily focused on researching and interpreting the maritime aspect of the War of 1812,

a conflict between Great Britain and the United States that occurred between 1812 and 1815. However we are interested in Canadian maritime themes from 1763 to Confederation.

See the resources below for more on the War, ship building, naval technology, and seamanship.

Recommended Reading

~ Books that teach us, inspire us, and let our imaginations sail away ~Purchase these books through the Amazon link to support the SocietyArticles by Society Members

Post-War Psyche

Posted February 15 2021

The history of HMS Psyche and the years immediately following the war are just as interesting as the war itself. The way the British and Americans rapidly reduced arms and rebuilt shipping on the Great Lakes to a state of peace and trade took a great deal of effort, overseen by Commodore Sir Edward Owen.

On December 25, 1814, HMS Psyche was launched at Kingston Royal Navy Dockyard. The war was over with the signing of the Treaty of Ghent, the day before. Of course, it took two months for news of the peace to reach Kingston. When it did arrive, Psyche no longer had a purpose.

It is interesting to note that as of January 1815, Commodore Sir James Yeo had requested guns to complete the armaments of Psyche and Princess Charlotte, revealing that there was insufficient ordnance to equip them even after their launches. Yeo was so insistent on the armament of these vessels that he suggested the guns be taken from the batteries at Quebec. In fact, the paucity of guns was due to 30 of Psyche’s guns being taken by the American privateer Fox in September of 1814.

News of the peace arrived in Kingston on March 1. However, through 1815 and 1816 there was a perceived threat that the peace could collapse. Therefore Britain ensured a state of readiness in the years following the war. Yeo was recalled, and Commodore Edward Owen took his place. Owen was initially tasked with replacing Yeo to better persecute the war, but was subsequently tasked with ensuring the peace while standing down the Great Lakes fleet in a way that allowed for rapid remobilization.

Owen was born 1771 in Campobello, Nova Scotia and came from a naval family. Having spent a typical career entering service at age 9, Owen worked the French and Dutch coasts through the Napoleonic Wars, and was considered an expert in cutting out, coastal bombardment, and guerre de course. For his inshore work he was knighted and assigned to the Great Lakes station.

Owen arrived in Kingston on March 19 1815 after a trip by steam boat, bateau portage, and mud road. Upon arrival, he entered HMS Psyche and formally assumed command on March 22, moving to HMS St. Lawrence. Psyche was returned to Captain Peter Fisher. This made Psyche flagship for two days! Yeo was relieved and was invited by US Commodore Isaac Chauncy to go home to England via Sacketts Harbour and New York.

Owen picked up where Yeo left off, championing Yeo’s recommended strategy to re-establish the naval presence on Lake Erie with a new base at Turkey Point; completing two first rate ships at Kingston; construct a frigate at Penetanguishene; and, construct a new base at Isle Au Noix on Lake Champlain with three more frigates (which Owen replaced with a plan for gunboats). Another unfinished project was the other three pre-fabricated vessels, a frigate (Prompte, sister ship to Psyche) and two brigs. The frames were sitting in a storehouse in Montreal. Due to the expense of transporting the materials to Kingston or Isle Aux Noix, Owen ordered the brigs assembled in Montreal and completed in Halifax, while the frigate parts were sold.

Meanwhile, the Americans were busy laying up all the vessels on the lakes, except Jones on Lake Ontario and Linnet on Lake Champlain. By the summer most of the US vessels capable of floating had been sold off. Their ships of the line at Sacketts Harbour remained on the stocks until the 1880s.

As the lakes unfroze and opened up for sailing in April 1815, Owen was focused on returning troops back to England. Initially Montreal (formerly Wolfe) and Prince Regent were disarmed and used for this purpose. Issues with many of the ships and the shipyard arose at this time:

• The gun carriages for St. Lawrence were deemed too short for the guns and needed to be replaced

• Montreal was found to be extremely leaky

• Princess Charlotte was too short of compliment to actually sail

• Psyche was still missing gun carriages

• The harbour in Kingston was becoming too crowded for the ships still on the stocks

In an environment where Britain was desperate to shed expenses after 22 years of war, the army retracting back to England, and the Navy back home laid up in ordinary, Owen was under tremendous pressure to secure the peace on a budget. The Lake Ontario fleet was converted to ship troops from Niagara to Kingston, from there to board gunboats for Montreal and transshipment to England. Prince Regent, Psyche, Montreal and Niagara (formerly Royal George) were tasked with the Lake Ontario leg of the trip, which was achieved by early June. Prince Regent ran aground in the process, taking three days to get free. Commodore Owen remarked that Psyche “sails faster than any ship on Lake Ontario.” Meanwhile the Glengarry Light Infantry was transported from Kingston to York in the same four ships. In all, 28,000 troops and RN personnel embarked transports at Quebec and set sail for home by mid-July.

Owen then turned his attentions to surveying the lakes for new bases and storage places for laid up ships. He also ordered a detailed survey of the ships in Kingston by Thomas Strickland, from which we get most of our information on hull design today. Strickland was one of the builders at Kingston dockyard and the builder of Psyche. The survey revealed the divergent outcomes of multiple builders in Kingston.

Owen still supported keeping a large fleet in ordinary during the peace, with only one warship per lake on active service. He determined that Psyche,, Princess Charlotte, and St. Lawrence would be laid up for future use. Niagara and Star, and later a new Charwell, would be relegated to transporting troops and stores in future years. Psyche was housed over by July 1815

Meanwhile Sir Charles Bagot was engaged in discussions with the Americans from mid-August to limit naval activity on the Great Lakes, which would eventually become the Rush-Bagot Treaty of 1816. Therefore Owen was discouraged from initiating new ships while the discussions were ongoing.

During June and July, the plan for downsizing the personnel of the naval establishment was set into motion. The volunteers of the previous Provincial Marine were released, and in June Captain Peter Fisher (in command of Psyche) departed with 350 sailors for Quebec. Desertion on the lakes after the war was a major problem, contributing to the mandated reduction in force faster than was planned. In May alone, over 100 men had deserted in Kingston. Admiralty directed Owen to replace sailors with local volunteers, and rendezvous points were set up in Kingston, Quebec, and Montreal. No more than 67 recruits were gathered, mostly from Quebec. A fascinating rotating tour of duty was set up, rotating men amongst the upper lakes and Lake Ontario, with a final reward of land in Upper Canada.

In October the remaining ships were housed over, their masts and rigging taken down, and the hatches covered. Repairs were effected to Prince Regent, Psyche, Niagara, Montreal, and Charwell (now a floating magazine), despite most being relatively new ships. Masts were stored in the ‘mast pond’ next to the dock yard to prevent drying out. No one was to stay aboard, and the ships were inspected, pumped, and heated twice a week. St. Lawrence was converted to a floating barracks. The first rates on the stocks were tarred but unfinished.

Owen’s last project was to encourage the building of a steamboat to ply the St. Lawrence to Kingston, which could assist in supplying Kingston from Montreal, a project the Americans already had a head start on. Psyche may have been a candidate for this enterprise, but it is unclear if another vessel was found or if the project was completed at all.

Owen departed the station November 5, leaving behind a greatly downsized, more economical force on the lakes. It was recognized that American infrastructure would only improve with time, and if there were another war, they would likely cut off the St. Lawrence and outperform the British shipyards on the lakes, and win superiority quickly. Command of the lakes fell to Captain William Owen, brother of Sir Edward.

The Rush-Bagot treaty was signed in 1817, formalizing the reduction in armament on the great lakes, but both sides built forts (such as Fort Henry) and canals (such as the Rideau) to secure their interests in case of future conflict. A small establishment of personnel was maintained at Kingston to manage the ships in ordinary. Images of Kingston in 1816 and afterwards show the ships still in ordinary. In 1819 Commodore Barrie, now in charge of the naval presence in Upper Canada, surveyed the ships and found dry rot and leaks in all of them. The Navy Board sent two surveyors in 1820 that came to similar conclusions, and recommended gradual rebuilds for Psyche, Niagara, Star, and Netley (Formerly Prince Regent).

The stone frigate (a stone building) was built in the Navy yard in 1820 to store key components of the ships. Psyche, Niagara, Star, and Netley were hauled out of the water, but no further repairs were undertaken. In 1831, Barrie was ordered to sell off the ships still afloat. They were advertised in the Kingston Chronicle, but there were no bidders, except for St. Lawrence, which was sold to a brewery and towed west to serve as a dock, where she sank and rests today. In 1834 the naval base at Kingston was shut down and all remaining naval stores were sold by 1836, but the hulls remained.

There was a brief resurgence of naval presence in Kingston with the 1837 Upper Canada Rebellion, during which the Navy yard was reopened, but was still full of derelict hulls, including three frigates, likely one of which was Psyche. The derelicts were considered an impediment to the use of the yard again. In 1841 a Royal Marine reported that the hulls had crumbled to pieces, been broken up, or sunk.

As for Psyche, in 1816, the ship is clearly marked in a survey of Navy Bay, afloat and in ordinary. Different researchers have come up with different fates: one suggests the hulk being sold. Mark Lardas (Great Lakes Warships) claims the hulk was put up for sale in 1833 but there were no buyers, and she sank at her moorings in the late 1830s. A third states the vessel was taken to Deadman Bay off Kingston and sunk there. Jonathan Moore in Coffins of the Brave writes that as late as 1836, Psyche was still in frame on a slip and was never replanked and relaunched, so could not have been sunk. This would be consistent with the accounts from 1837.

HMS Psyche was built in a trying age fraught with challenges and hardship for the common seaman. The approximately 150,000 men (and some women!) who manned the ships of the Royal Navy by the time of the War of 1812 had little to look forward to except monotonous routine, bitter weather, risk of disease and death (sound familiar?). The pay wasn’t great, often deferred, and regularly reduced once finally issued. Yet there are many recorded instances of common seamen volunteering and serving in the Navy for decades. There were some compelling reasons to enter into and stay in the Navy life.

Regular food in substantial quantity, the chance to move up through the ranks, or an escape from crushing poverty or criminal condemnation ashore were incentives. Camaraderie, adventure, and a chance for glory also played into it. There was also the potential of prize money, which having just read ‘Post Captain’ in the Aubrey-Maturin series, is top of mind for me today.

Prize money encompassed a ‘bonus’ payment for the capture of enemy ships or the destruction of enemy shipping or stores. The value of the prize money was determined by the Prize Court, which adjudicated the legality of the prize (neutral ships were particularly sticky) and the value. The value included the captured ship herself, head money representing the crew compliment (£5 a head), and the value of any stores or goods within her. There were also legal and agency fees to pay, especially if a captain was not able to attend the prize court and/or wished to draw upon the prize money before adjudication, in which case the prize agent would advance a discounted amount of money then collect the bulk from the courts and pocket the difference. Some agents absconded with the money altogether.

The rules and regulations for prize money were enacted by Parliament at the beginning of each conflict, and rarely updated through the course of the 18th century. In 1793, the commanding admiral, captain, wardroom and gunroom officers received 3/4 the value of the prize money, and the common sailors had to settle for the remaining 1/4. An update in 1808 modified the distribution between captains and admirals, reduced the classes for distribution, and gave 1/2 the value of the prize to the junior officers and seamen.

Therefore in 1808 until 1815, prize money was distributed by class as follows:

1/4 - Captain – of which 1/3 would be given to any qualifying admiral

1/8 - Wardroom Officers and Standing Officers (Lieutenants, Captain of Marines, Master, Purser, Surgeon, Chaplain, Gunner, Bos’un, Carpenter)

1/8 - Senior Warrant Officers (Midshipmen, Clerk, Armourer, Ropemaker, Caulker, Sailmaker, Cox’un, Yeomen)

1/2 - Junior Officers (cook, carpenter’s crew, etc.), all seamen, landsmen and boys

….. the portion to be distributed equally between all members of each class.

Pay for officers in 1814 depended on the ship they were assigned to. Psyche, being a 5th rate 54-gun frigate with an expected crew of 280 sailors, would have warranted a post captain and 3 to 4 lieutenants. As there was only one post-captain on the Great Lakes (Commodore Sir James Yeo), all the ships were commanded by a variety of lieutenants (dubbed ‘commanders’ when in command of a vessel). It is unclear who would have commanded Psyche had the war continued on, but let’s assume Yeo would have assigned one of the lieutenants that came with him up the St. Lawrence in 1813. Without a captain, Psyche would not have been rated and would have been deemed a ‘sloop of war’ with a commander.

A commander of a sloop of war would normally be paid 272 pounds, 19 shillings, and 7 pence a year. After income tax, his net salary would be 245 pounds 13 shillings 4 pence. An ordinary seaman would get 13 pounds, 10 shillings per year, assuming it was actually paid out in full, which was not always the case. Our beloved cook would be paid 12 pounds, 4 shillings per year.

Prize money offered an incredible opportunity to supplement these meagre wages. By 1814 there was minimal shipping on the Great Lakes, given all the merchant vessels had been requisitioned into the respective naval fleets, or had been captured or sunk by storms. If Psyche were able to take an American transport vessel, such as the sloop Asp, with a crew of 45, undamaged and laden with military stores, Asp might fit into the ‘average’ value of prizes captured by the Royal Navy at the time. Daniel K. Benjamin’s lovely essay “Golden Harvest: The British Naval Prize System” pegs the average value of a Royal Navy prize as £2300. (This essay is now included in the ‘Documents’ section for your interest.)

So, £2300 would be distributed amongst the Psyche’s crew as follows:

Commander - £575

Wardroom and Standing Officers: £287.10s, to be distributed to each member of this class

Snr Warrant Officers - £287.10s, to be distributed to each member of this class

Jr Officers and Crew - £1150, to be distributed to each member of this class

Let’s say of the 280 officers and crew, there were 30 officers of the first three classes, and the remaining compliment of 250 was made up of sailors, marines, junior officers, boys, etc. That £1150 becomes £4.12s each! It’s not much, but it amounts to about 3 month’s worth of wages for a single day’s work for the average sailor. You tell me if that’s a compelling offer!

Images:

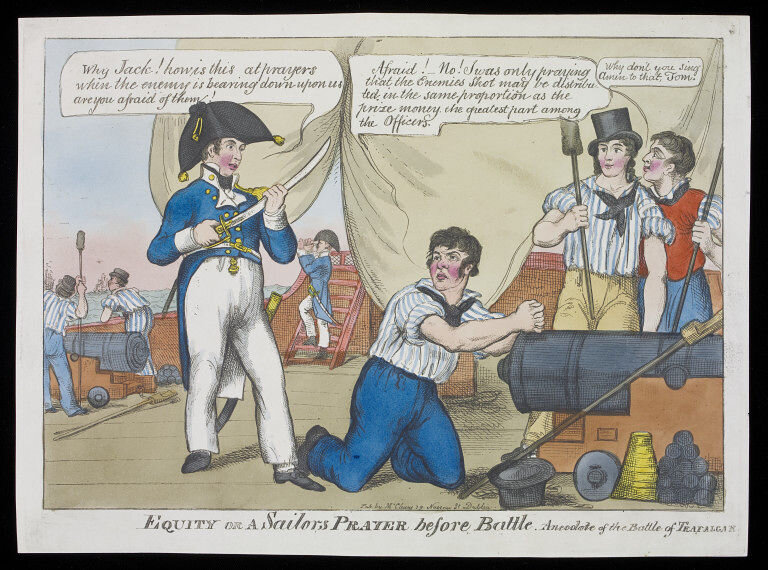

Cartoon: A sailor prays that the distribution of enemy shot follows the same distribution formula for prize money! This cartoon seems to follow the Battle of Trafalgar so likely precedes the 1808 revisions to the prize money formula.

Coinage: This shows what a sailor’s share aboard HMS Psyche would look like, based on the calculation in this post. 4 guineas and 6 shillings. Note: 1 gold guinea is worth £1.1s.

Frigates: The ships of Yeo’s squadron attack Oswego in 1814. In the foreground is HMS Prince Regent, a 54 gun frigate built in Kingston, similar to HMS Psyche.

Sloop: An American sloop, similar to USS Asp.

Political Cartoons During the War of 1812

Posted February 6, 2020

I’ve always been interested in the political cartoons of the late 18th/early 19th century. They say a lot about common perceptions held at the time, but also radical or subversive opinions, just as they do today. The Royal Navy appears in many of them as both the saviour of England, and the lovable buffoon of Jack Tar ashore.

Of particular interest to us are two cartoons generated in 1798 and 1814, presented here. The 1798 cartoon titled “High Fun for John Bull” was authored by Thomas Rowlandson, a London cartoonist. In this image is illustrated caricatures of the French, Spanish, and Dutch providing ships and guns to a ‘Dutch oven’, wherein they are transmuted to British ownership represented by John Bull and Jack Tar. In 1798 Britain was at war with all three and yet still ruled the waves, snapping up the shipping of each, making the fortunes of many a crew aboard His Majesty’s ships. Jack Tar walks away with the finished result of the ‘baking’, while John Bull cracks the whip for the Dutch to make more ships on behalf of the French, ostensibly to then capture at sea. A full transcript of the cartoon can be read here:

Later in 1814, an American cartoonist named William Charles channelled the 1798 cartoon and created “John Bull Making a New Batch of Ships to Send to the Lakes.” In this cartoon, John Bull / George III rushes to ‘bake’ a new batch of ships to send to the Great Lakes after the Battle of Lake Erie. At this time, one of the ships he is ‘baking’ would, in actuality, be HMS Psyche, which was pre-fabricated in England in 1813 and shipped in pieces to Kingston for assembly over 1814. John Bull’s assistants include a ragged man representing France (as an ally following Napoleon’s first exile) and two presumably British citizens who warn of losses of guns and ships destined for the lakes, taken by American privateers at sea. The British citizen expresses a desire to keep the guns and ships at home, lest the Americans ‘make fun’ (i.e. sport) by taking them on the high seas. A full transcript can be found here:

https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/42795

Both cartoons likely speak to prevailing public opinion of opposing naval forces. Interestingly, both also offer virtually the same caricature of the Frenchman with the dough trough, despite being from different years and different nationalities. These are just some political cartoons from that time period that draw on the imagery of ‘baking’ something up, be it a cockamamie invasion, minting alliances between continental bedfellows, or installing new kings in European courts.